January 3, 2020 — Speling errors and errors grammar are nearly extinct in published content. Data errors, however, are prolific.

By data error I mean one the following errors: a statement without a backing dataset and/or definitions, a statement with data but a bad reduction(s), or a statement with backing data but lacking integrated context. I will provide examples of these errors later.

The hard sciences like physics, chemistry and most branches of engineering have low tolerance for data errors. But outside of those domains data errors are everywhere.

Fields like medicine, law, media, policy, the social sciences, and many more are teeming with data errors, which are far more consequential than spelling or grammar errors. If a drug company misspells the word dockter in some marketing material the effect will be trivial. But if that material contains data errors those often influence terrible medical decisions that lead to many deaths and wasted resources.

If Data Errors Were Spelling Errors

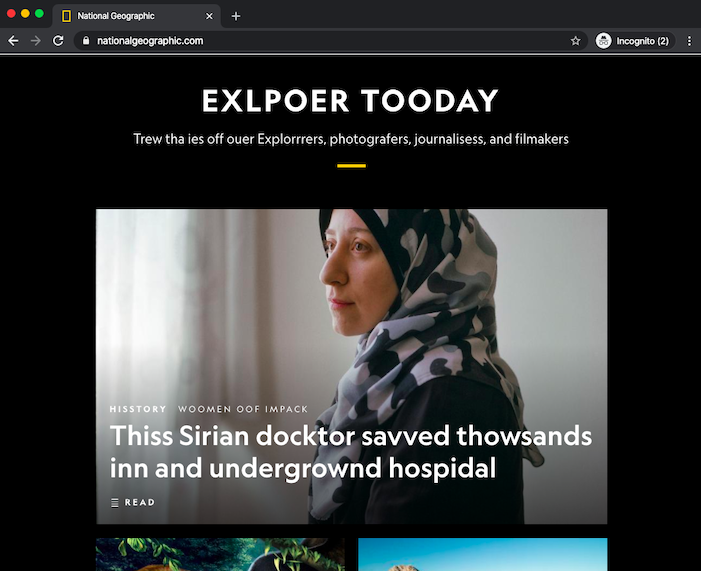

You would be skeptical of National Geographic if their homepage looked like this:

We generally expect zero spelling errors when reading any published material.

Spell checking is now an effortless technology and everyone uses it. Published books, periodicals, websites, tweets, advertisements, product labels: we are accustomed to reading content at least 99% free of spelling and grammar errors. But there's no equivalent to a spell checker for data errors and when you look for them you see them everywhere.

The Pandemic: An Experiment

Data errors are so pervasive that I came up with a hypothesis today and put it to the test. My hypothesis was this: 100% of "reputable" publications will have at least one data error on their front page.

Method

I wrote down 10 reputable sources off the top of my head: the WSJ, The New England Journal of Medicine, Nature, The Economist, The New Yorker, Al Jazeera, Harvard Business Review, Google News: Science, the FDA, and the NIH.

For each source, I went to their website and took a single screenshot of their homepage, above the fold, and skimmed their top stories for data errors.

Results

In the screenshots above, you can see that 10/10 of these publications had data errors front and center.

Breaking Down These Errors

Data errors in English fall into common categories. My working definition provides three: a lack of dataset and/or definitions, a bad reduction, or a lack of integrated context. There could be more, this experiment is just a starting point where I'm naming some of the common patterns I see.

The top article in the WSJ begins with "Tensions Rise in the Middle East". There are at least 2 data errors here. First is the Lack of Dataset error. Simply put: you need a dataset to make a statement like that. There is no longitudinal dataset in that article on tensions in the Middle East. There is also a Lack of Definitions. Sometimes you can not yet have a dataset but at least define what a dataset would be that could back your assertions. In this case we have neither a dataset nor a definition of what some sort of "Tensions" dataset would look like.

In the New England Journal of Medicine, the lead figure shows "excessive alcohol consumption is associated with atrial fibrillation" between 2 groups. One group had 0 drinks over a 6 month period and the other group had over 250 drinks (10+ per week). There was a small impact on atrial fibrillation. This is a classic Lack of Integrated Context data error. If you were running a lightbulb factory and found soaking lightbulbs in alcohol made them last longer, that might be an important observation. But humans are not as disposable, and health studies must always include integrated context to explore whether there is something of significance. Having one group make any sort of similar drastic lifestyle change will likely have some impact on any measurement. A good rule of thumb is anything you read that includes p-values to explain why it is significant is not significant.

In Nature we see the line "world's growing water shortage". This is a Bad Reduction, another very common data error. While certain areas have a water shortage, other areas have a surplus. Any time you see a broad diverse things grouped into one term, or "averages", or "medians", it's usually a data error. You always need access to the data, and you'll often see a more complex distribution that would prevent broad true statements like those.

In The Economist the lead story talks about an action that "will have profound consequences for the region". Again we have the Lack of Definitions error. We also have a Forecast without a Dataset error. There's nothing wrong with making a forecast--creating a hypothetical dataset of observations about the future--but one needs to actually create and publish that dataset and not just a vague unfalsifiable statement.

The New Yorker lead paragraph claims an event "was the most provocative U.S. act since...". I'll save you the suspense: the article did not include a thorough dataset of such historical acts with a defined measurement of provocative. Another Lack of Dataset error.

In Al Jazeera we see "Iran is transformed" and also a Bad Reduction, Lack of Dataset and Lack of Definition errors.

Harvard Business Review has a lead article about the Post-Holiday funk. In that article the phrase "research...suggests" is often a dead giveaway for a Hidden Data error, where the data is behind a paywall and even then often inscrutable. Anytime someone says "studies/researchers/experts" it is a data error. We all know the earth revolves around the sun because we can all see the data for ourselves. Don't trust any data you don't have access to.

Google News has a link to an interesting article on the invention of a new type of color changing fiber, but the article goes beyond the matter at hand to make the claim: "What Exactly Makes One Knot Better Than Another Has Not Been Well-Understood – Until Now". There is a Lack of Dataset error for meta claims about the knowledge of knot models.

The FDA's lead article is on the Flu and begins with the words "Most viral respiratory infections...", then proceeds for many paragraphs with zero datasets. There is an overall huge Lack of Datasets in that article. There's also a Lack of Monitoring. Manufacturing facilities are a controlled, static environment. In uncontrolled, heterogeneous environments like human health, things are always changing, and to make ongoing claims without having infrastructure in place to monitor and adjust to changing data is a data error.

The NIH has an article on how increased exercise may be linked to reduced cancer risk. This is actually an informative article with 42 links to many studies with lots of datasets, however the huge data error here is Lack of Integration. It is very commendable to do the grunt work and gather the data to make a case, but simply linking to static PDFs is not enough—they must be integrated. Not only does that make it much more useful, but if you've never tried to integrate them, you have no idea if the pieces actually will fit together to support your claims.

While my experiment didn't touch books or essays, I'm quite confident the hypothesis will hold in those realms as well. If I flipped through some "reputable" books or essayist collections I'm 99.9% confident you'd see the same classes of errors. This site is no exception.

The Problem is Language Tools

I don't think anyone's to blame for the proliferation of data errors. I think it's still relatively recent that we've harnessed the power of data in specialized domains, and no one has yet invented ways to easily and fluently incorporate true data into our human languages.

Human languages have absorbed a number of sublanguages over thousands of years that have made it easier to communicate with ease in a more precise way. The base 10 number system (0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9) is one example that made it a lot easier to utilize arithmetic.

Taking Inspiration from Programming Language Design

Domains with low tolerance for data errors, like aeronautical engineering or computer chip design, are heavily reliant on programming languages. I think it's worthwhile to explore the world of programming language design for ideas that might inspire improvements to our everyday human languages.

Some quick numbers for people not familiar with the world of programming languages. Around 10,000 computer languages have been released in history (most of them in the past 70 years). About 50-100 of those have more than a million users worldwide and the names of some of them may be familiar to even non-programmers such as Java, Javascript, Python, HTML or Excel.

Not all programming languages are created equal. The designers of a language end up making thousands of decisions about how their particular language works. While English has evolved with little guidance over millennia, programming languages are often designed consciously by small groups and can evolve much faster.

Often the designers change a language to make it easier to do something good or harder to do something bad.

Sometimes what is good and bad is up to the whims of the designer. Imagine I was an overly optimistic person and decided that English was too boring or pessimistic. I may invent a language without periods, where all sentences must end with an exclamation point! I'll call it Relish!

Most of the time though, as data and experience accumulates, a rough consensus emerges about what is good and bad in language design (though this too seesaws).

Typed Checked Languages

One of the patterns that has emerged as generally a good thing over the decades to many languages is what's called "type checking". When you are programming you often create buckets that can hold values. For example, if you were programming a function that regulated how much power a jet engine should supply, you might take into account the reading from a wind speed sensor and so create a bucket named "windSpeed".

Some languages are designed to enforce stricter logic checking of your buckets to help catch mistakes. Others will try to make your program work as written. For example, if later in your jet engine program you mistakenly assigned the indoor air temperature to the "windSpeed" bucket, the parsers of some languages would alert you while you are writing the program, while with some other languages you'd discover your error in the air. The former style of languages generally do this by having "type checking".

Type Checking of programming languages is somewhat similar to Grammar Checking of English, though it can be a lot more extensive. If you make a change in one part of the program in a typed language, the type checker can recheck the entire program to make sure everything still makes sense. This sort of thing would be very useful in a data checked language. If your underlying dataset changes and conclusions anywhere are suddenly invalid, it would be helpful to have the checker alert you.

Perhaps lessons learned from programing language design, like Type Checking, could be useful for building the missing data checker for English.

A Blue Squiggly to Highlight Data Errors

Perhaps what we need is a new color of squiggly:

✅ Spell Checkers: red squiggly

✅ Grammar Checkers: green squiggly

❌ Data Checkers: blue squiggly

If we had a data checker that highlighted data errors we would eventually see a drastic reduction in data errors.

If we had a checker for data errors appear today our screens would be full of blue. For example, click the button below to highlight just some of the data errors on this page alone.

How Do We Reduce Data Errors?

If someone created a working data checker today and applied it to all of our top publications, blue squigglies would be everywhere.

It is very expensive and time consuming to build datasets and make data driven statements without data errors, so am I saying until we can publish content free of data errors we should stop publishing most of our content? YES! If you don't have anything true to say, perhaps it's best not to say anything at all. At the very least, I wish all the publications above had disclaimers about how laden with data errors their stories are.

Of course I don't believe either of those are likely to happen. I think we are stuck with data errors until people have invented great new things so that it becomes a lot easier to publish material without data errors. I hope we somehow create a data checked language.

I still don't know what that looks like, exactly. I spend half my work time attempting to create such new languages and tools and the other half searching the world to see if someone else has already solved it. I feel like I'm making decent progress on both fronts but I still have no idea whether we are months or decades away from a solution.

While I don't know what the solution will be, I would not be surprised if the following patterns play a big role in moving us to a world where data errors are extinct:

1. Radical increases in collaborative data projects It is very easy for a person or small group to crank out content laden with data errors. It takes small armies of people making steady contributions over a long time period to build the big datasets that can power content free of data errors.

2. Widespread improvements in data usability. Lots of people and organizations have moved in the past decade to make more of their data open. However, it generally takes hours to become fluent with one dataset, and there are millions of them out there. Imagine if it took you hours to ramp on a single English word. That's the state of data usability right now. We need widespread improvements here to make integrated contexts easier.

3. Stop subsidizing content laden with data errors. We grant monopolies on information and so there's even more incentive to create stories laden with data errors—because there are more ways to lie than to tell the truth. We should revisit intellectual monopoly laws.

4. Novel innovations in language. Throughout history novel new sublanguages have enhanced our cognitive abilities. Things like geometry, Hindu-Arabic numerals, calculus, binary notation, etc. I hope some innovators will create very novel data sublanguages that make it much easier to communicate with data and reduce data errors.

Have you invented a data checked language, or are working on one? If so, please get in touch.