December 28, 2023 — I thought we could build AI experts by hand. I bet everything I had to make that happen. I placed my bet in the summer of 2022. Right before the launch of the Transformer AIs that changed everything. Was I wrong? Almost certainly. Did I lose everything? Yes. Did I do the right thing? I'm not sure. I'm writing this to try and figure that out.

Symbols

Leibniz is probably my favorite thinker. His discoveries in mathematics and science are astounding. Among other things, he's the thinker credited with discovering Binary Notation--that ones and zeros are all you need to represent anything. In my opinion this is perhaps the most incredible idea in the world. As a kid I grew up surrounded by magic digital technologies. To learn that truly all this complexity was built on top of the simplicity of ones and zeroes astounded me. Simplicity and complexity in harmony. What makes Leibniz stand out more to me is not just his discoveries but how what he was really after was a characteristica universalis, a natural system for representing all knowledge that would allow for the objective solving of questions across science.

I wanted to be like Leibniz. Leibniz had extreme IQ, work ethic, and ability to take intellectual risks. Unfortunately I have only above average IQ and inconsistent work ethic. If I was going to invent something great, it would have to be because I took more risks and somehow got lucky.

Eventually I got my chance. Or at least, what I took to be my chance.

Computers ultimately operate on instructions of ones and zeroes, but those that program computers do not write in ones and zeroes. They did in the beginning, when computers were a lot less capable. But then programmers invented new languages and programs that could take other programs written in these languages and convert them into ones and zeroes ("compilers").

Over time, a common pattern emerged. In addition to everything being ones and zeroes at some point, at some point everything would also be digital "trees" (simple structures with nodes and branches). Binary Notation can minimally represent every concept in ones and zeroes, was there some minimal notation for the tree forms of concepts? And if there were, would that notation be mildly interesting, or somehow really powerful like Binary Notation?

This is an idea I became obsessed with. I came across it by chance, when I was still a beginner programmer. I was trying to make a programming language as simple as possible and realized all I needed was enough syntax to represent trees. If you had that, you could represent anything. Eureka! I then spent years trying to figure out whether this minimal notation was mildly interesting or really useful. I tried to apply it to lots of problems to see if it solved anything.

If your syntax can distinguish symbols and define scopes you can represent anything.

The Book

One day I imagined a book. Let's call it The Book. It could be billions of pages long. It would be lacking in ornamentation. The first line would be a mark for "0". The second line would be a mark for "1". You've just defined Binary Notation. You could then use those defined symbols to define other symbols.

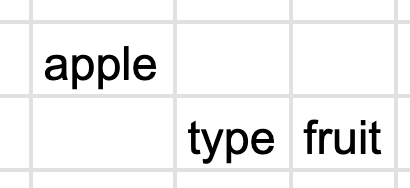

In the first hundred pages you might have the line "8 1000" to define the decimal number 8. In the first ten thousand pages you might have the line "a 97" to define the character "a" as part of defining ASCII. In the first million pages you might have the word "apple", and in the first hundred million you might have defined all the molecules that are present in an apple.

The primary purpose of The Book would be to provide useful models for the world outside The Book. But a lot of the pages would go to building up a "grammar" which would dictate the rules for the rest of the symbols in The Book and connect concepts together. In a sense the grammar compresses the contents of The Book, minimizing not the number of bits needed but the number of symbols needed and the entropy of the cells on the pages that hold the symbols, and maximizing the comparisons that could be made between concepts. The notation and grammar rules would not be arbitrary but would be discovered as the most efficient way to define higher and higher level symbolic concepts, just as Boolean Algebra gives us the tools to build bigger and bigger efficient circuits. Boolean Algebra is not arbitrary but somehow arises from the laws of the universe, and so would this algebra for abstraction. It would implement ideas from mathematical domains such as Category and Type theory with surprisingly simple primitives. It was a new way to try and build the characteristica universalis.

The Book would be an encyclopedia. But it wouldn't just list concepts and their descriptions in a loosely connected way. It would build up every concept, so you could trace all of the concepts required by any other concept all the way down to Binary. Entries would look so simple but would abide by the grammar and every word in every concept would have many links. It would be a symbolic network.

You would not only have definitions of every concept, but comparability would be maximized. Wikipedia does a remarkable job of listing all the concepts in a space and concepts are weakly linked. But Wikipedia is primarily narratives and the information is messy. Comparability is nowhere near maximized.

The pieces would almost lock in place because each piece would influence constraints on other pieces--false and missing information would be easy to identify and fix.

Probably more than 100,000 people have researched and developed digital knowledge bases and expert systems. Those 100,000 probably came up with 1,000,000 ways to do it. If there were some simplest way to do it--a minimal Binary Notation and Boolean Algebra for symbols--that would work for any domain, perhaps that would lead to unprecedented collaboration across domains and a breakthrough in knowledge base powered experts.

Experts

It wasn't the possibility of having a multi-billion page book that excited me. It is what The Book could power. You would not generally read The Book like an encyclopedia, but it would power an AI expert you could query.

What is an expert? An expert is an agent that can take a problem, list all the options, and compare them in all the relevant ways so the best decision can be made. An expert can fail if it is unaware of an option or fails to compare options correctly in all of the relevant ways.

Over the years I've thought a lot about why human experts go wrong in the same way over and over. As Yogi Berra might say, "You can trust the experts. Except when you can't". When an expert provides you with a recommendation, you cannot see all the concepts they considered and comparisons they made. Most of the time it doesn't matter because the situation at hand has a clear best solution. In my experience the experts are mostly right, with the occasional innocent mistake. You can greatly reduce the odds of an innocent mistake by getting multiple opinions. But sometimes you are dealing with a problem with no standout solution. In these cases biased solutions flood the void. You can shuffle from "expert" to "expert", hoping to find "the best expert" with a standout solution. But at that point you probably won't do better than simply rolling a dice.

The Edge of Knowledge

No one is an expert past the line of what is known. Even more of a problem is that it is impossible to see where that line is. If we could actually make something like The Book, we could see that line. A digital AI expert, which could show not only all the important stuff we know, but also what we don't know, would be the best expert.

In addition to powering AI experts that could provide the best guidance, The Book could aid in scientific discoveries. Anyone would be able to see the edge of knowledge in any domain and know where to explore next. Because everything would be built in the same universal computable language, you could do comparisons not only within a domain, but also across domains. Maybe there are common meta patterns in diverse symbolic domains such as physics, watchmaking, and hematology that are undiscovered but would come to light in this system. People who had good knowledge about knowledge could help make discoveries in a domain they knew little about.

Dreaming of Digital AI Experts

I was extremely excited about this idea. It was just like my favorite idea--Binary Notation--endless useful complexity built up from simplicity. We could build digital experts for all domains from the same simple parts. These experts could be downloadable and available to everyone.

Imagine how trustworthy they would be! No need to worry about hidden biases in their answers--biases are also concepts that can be measured and would be included in The Book. No "blackbox" opaque collections of trained matrices. Every node powering these AIs would be a symbol reviewable by humans. There would be a massive number of pages, to be sure, but you would almost always query it, not read it. Mostly you'd consume it via data driven visualizations to your questions, rather than as pages of text.

No one can know everything, but imagine if anyone could see everything known! I don't mean see all the written or digital information in the world. That would be so overwhelming and little more useful than staring at white noise. The symbols in The Book would be more like the prime numbers. All numbers are made up of prime numbers but prime numbers make up ~0% of all numbers. The Book would be the slim fraction containing the key information.

You wouldn't be able to read everything but you would be able to use a computer to instantly query over everything.

Everything could be printed out on a single scroll. But in practice you would have a digital collection of files containing concepts which would have answers to questions about those concepts. An academic paper would include a change request to a collection. It would add new files or update some lines in existing files. For example, I just read a paper about an experiment that looks at how a genetic mutation might exacerbate a psychiatric condition. The key categories of things dealt with were SNVs, Proteins, Organelles, Pathways, and Psychiatric Conditions. Currently there are bespoke databases for each of these things. None of them are implemented in the same way. If they were, it would be easy to actually see the holistic story and contributions of the paper. With this system, you would see what gaps were being filled, or what mistakes corrected.

This was a vague vision at first. I thought a lot about the AI experts you could get if you had The Book. I was playing with all the AIs at the time and tried to think backwards from the end state. What would the ideal AI expert look like?

Interface questions aside, it would need two things. It would need to know all the concepts and maximize comparability between them. But for trust, it would also need to be able to show that it has done so.

In the long run I thought that the only way to absolutely trust an AI expert would be if there were an human inspectable knowledge base behind it that powered calculations. The developments in AI were exciting but I thought in the long run the best AI would need something like The Book.

First Attempts

My idea was still a hunch, not a proof, and I set out building prototypes.

I tried a number of times to build things up from "0 1". That went nowhere. It was very hard to find any utility from such a thing or get feedback on whether one was building in the right direction. I think this was the same way Leibniz tried to build his characteristica universalis. It was a doomed approach.

By 2020 I had switched to trying to make something high level and useful from the beginning. There was no reason The Book had to be built in order. We had decimal long before we had binary, even though the latter is more primitive. The later "pages" are generally the ones where the most handy stuff would be. So pages 10 million to 11 million could be created first by practitioners, with earlier sections and the grammar filled in by logicians and ontological engineers over time.

There was also no reason that The Book had to built as a monolith. Books could be built in a federated fashion, useful standalone, and merged later to power a smarter AI. The universal notation would facilitate later merging so the sum would be greater than the parts. Imagine putting one book on top of another. Nothing happens. But with this system, you could merge books and there would suddenly be a huge number of new "synapses" connecting the words in each. The comparisons you could make go up exponentially. The resulting combination would be increasingly smarter and more efficient. So you could build "The Book" by building smaller books and combining them together.

With these insights I made a prototype called "TreeBase". I described it like so: "Unlike books or weakly typed content like Wikipedia, TreeBases are computable. They are like specialized little brains that you can build smart things out of."

At first, because of the naive file based approach, it was slow and didn't scale. But lucky for me, a few years later Apple came out with much faster computers. Suddenly my prototype seemed like it might work.

The Prototype

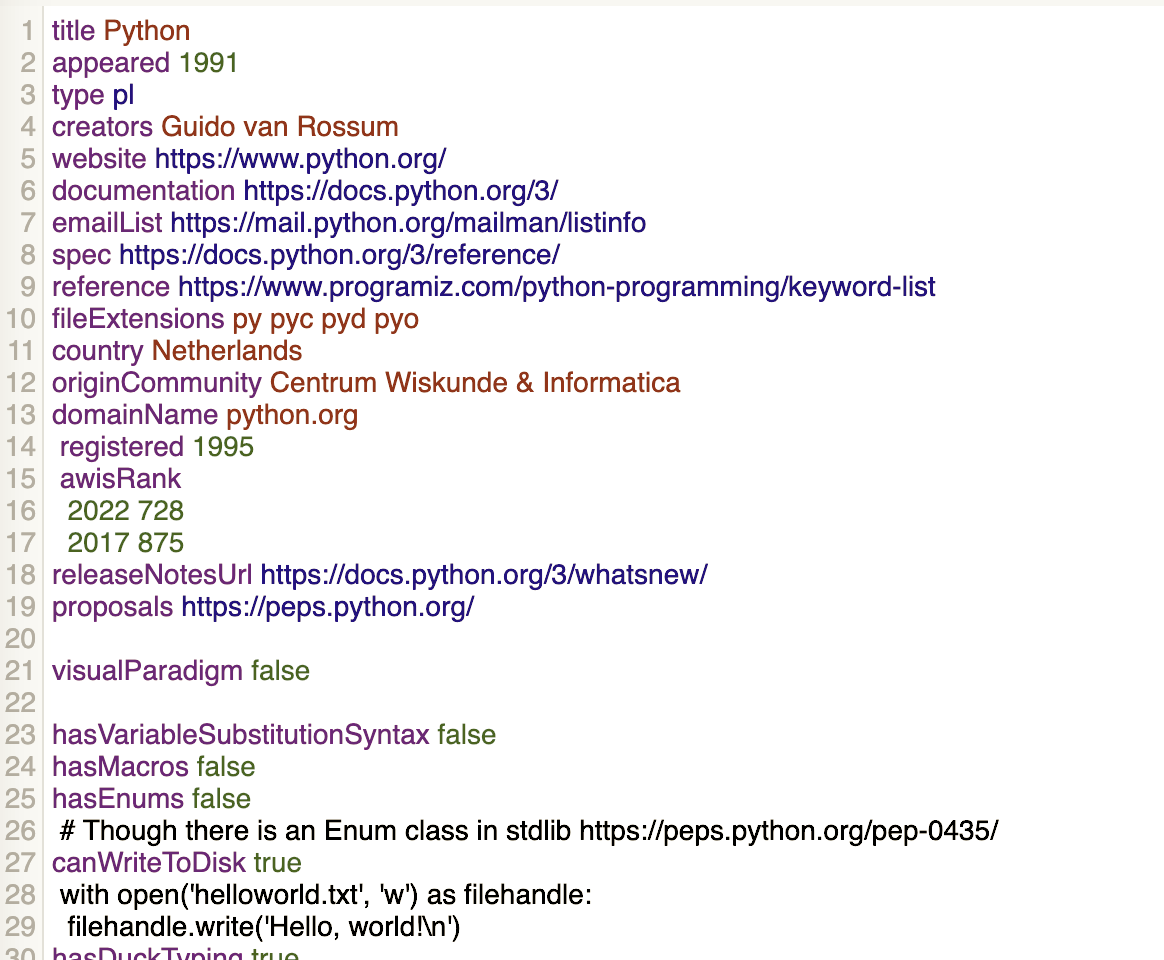

In the summer of 2022, I used TreeBase to to make "PLDB", a Programming Language DataBase. This site was an encyclopedia about programming languages. It was the biggest collection of data on programming languages, which was gathered over years by open source contributors and myself and reviewed by hand.

Part of the "Python" entry in PLDB. The focus is on computable data rather than narratives.

As a programming enthusiast I enjoyed the content itself. But to me the more exciting view of PLDB was as a stepping stone to the bigger goal of creating The Book and breakthrough AI experts for any domain.

It wasn't a coincidence that to find a symbolic language for encoding a universal encyclopedia I started with an encyclopedia on symbolic languages. I thought if we built something to first help the symbolic language experts they would join us in inventing the universal symbolic language to help everyone else.

PLDB was met with a good reception when I launched it. After years of tinkering, my dumb idea seemed to have potential! More and more people started to add data to PLDB and get value from it. To be clear, almost certainly the content was the draw, and not the new system under the hood. I enjoyed working on the content very much and did consider keeping PLDB as a hobby and forgetting the larger vision.

But part of me couldn't let that big idea go. Part of me saw PLDB as just pages 10 million to 11 million in The Book. PLDB was still far from showing the edge of knowledge in programming languages, but now I could see a clear path to that, and thought this system could do that for any domain. Part of me believed that the simple system used by PLDB, at scale, would lead to a better mapping of every domain and the emergence of brilliant new AI experts powered by these knowledge bases.

Scale

I understand how naive the idea sounds. Simply by adding more and more concepts and measurements to maximize comparability in this simple notational system you could map entire knowledge domains and develop digital AI experts that would be the best in the world! Somehow I believed my implementation would succeed where countless other knowledge base and expert systems had failed. My claims were very hand wavy! I predicted there would be emergent benefits, but I had little proof. It just felt like it would, from what I had seen in my prototypes.

Where would the emergent benefits come from in my system that wouldn't come from existing approaches?

Dimensions! Dimensions! Dimensions!

A dimension, which is symbolically just another word for column in a table of measurements, is a different perspective of looking at something. For example, a database about fruits might have one dimension measuring weight and another color. There's a famous Alan Kay quote about a change in perspective being worth 80 IQ points. That's not always the case, but you can generally bet adding perspectives increases one's understanding, often radically. A thing that surprised me when building PLDB was just how much the value of a dataset grew as the number of dimensions grew. New dimensions not only increased the number of insights you could make, sometimes radically, but also expanded opportunities to add even more promising dimensions. This second positive feedback loop seemed to be more powerful than I expected. Of course, it is easy to add a dimension in a normalized SQL database. Simply add a column or create a new table for the dimension with a foreign key to the entity. My thought was seemingly small improvements to the workflow of adding dimensions would have compounding effects.

Minimalism

I also thought minimalism would show us the way. Every concept in this system would have to adhere to the strictest rules possible. The system could encode any concept. So if the rules prevented a true concept from being added, the rules would be adjusted at the same time. The system was designed to be plain text backed by git to make system wide fixes a cinch. The natural form and natural algebra would emerge and be a forcing function that led us to the characteristica universalis. This would catapult this new system from mildly interesting to world changing. I believed if we just tried to build really really big versions of these things, we would discover that natural algebra and grammar.

However, there were a ton of details to get right in the core software. If you didn't get the infrastructure for this kind of system to a certain point then it would not compete favorably against existing approaches. Simplicity is timeless but scaling things is always complex. This system needed to pass a tipping point past which clever people would see the benefits and the idea would spread like fire.

It was simple enough to keep growing the tech behind PLDB slowly and steadily but I might never get it to that tipping point. If I was right and this was the path to building The Book and the best AI experts, but we never got there because I was too timid, that would be tragic! Was there a way I could move faster?

Version Two

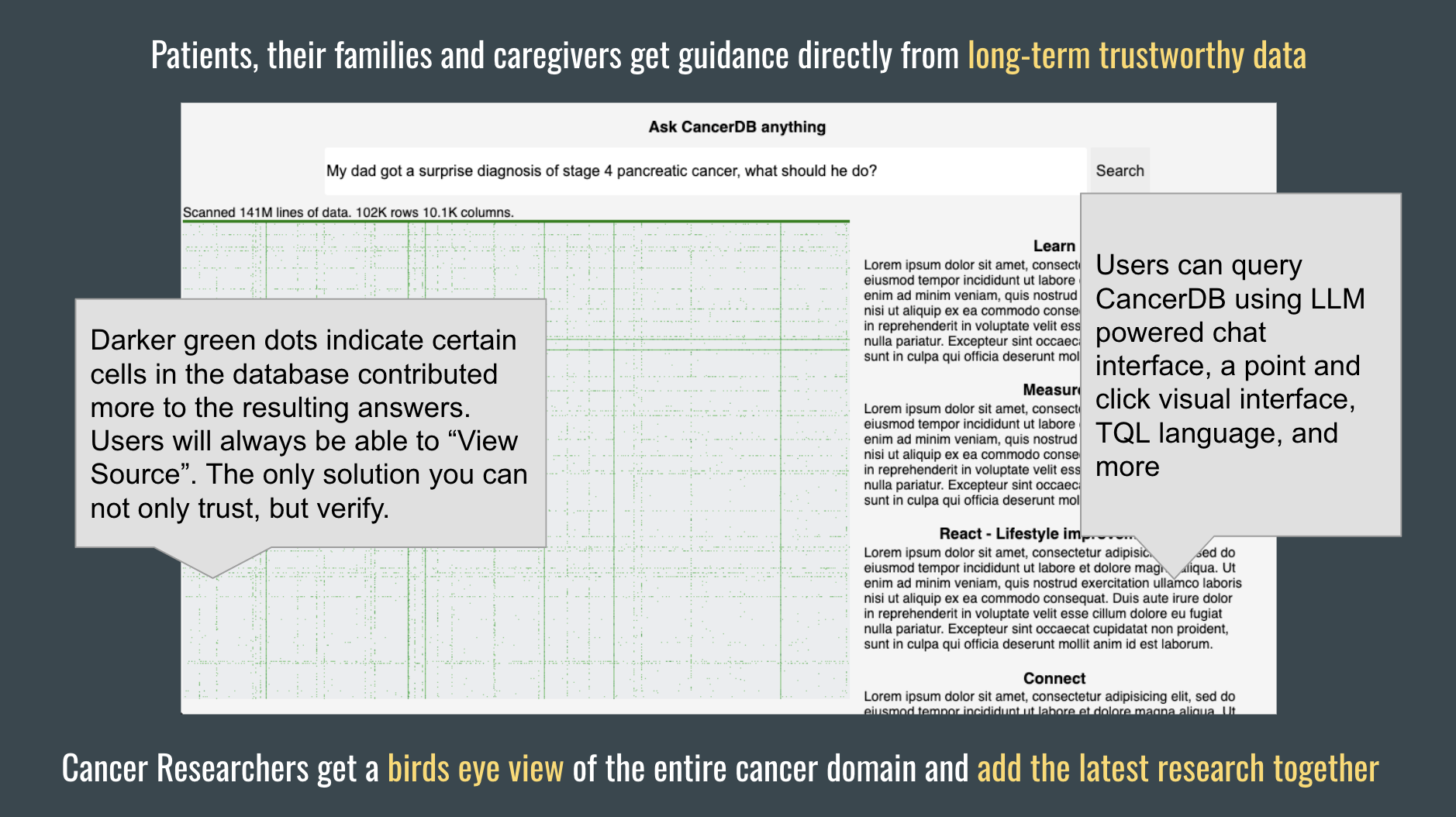

I had an idea. I had worked in cancer research for a few years so had some knowledge of that domain. In addition to PLDB, why not also start building CancerDB, building an expert AI for a domain that affects everyone in a life and death matter? Both required building the same core software, but it seemed like it would be 1,000x easier to get a team and resources to build an expert AI to help solve cancer rather than just improve programming languages. I could test my hunch that my system would really start to shine at scale and if it worked help accelerate cancer research in the process. It seemed like a more mathematically sound strategy.

The Business Model

Knowledge in this system was divided into simple structured blocks, like in the screenshots above. Blocks could contain two things. They could define information about the external world. And some could define rules for other blocks. The Book would come together block by block, like a great wall. The amount of blocks needed for this system to become intelligent would be very high. Some blocks were cheap to add, others would require original research and experiments. It would be expensive to add enough blocks to effectively map entire domains.

Like walls in the real world that have "Buy a Brick", we would have another kind of block, sponsor blocks, which would give credit to funders for funding the addition and upkeep of blocks. This could create a fast, intelligent feedback loop between funders and researchers. Because of the high dimensional nature of the data, and computational nature of the encoding, we would have new ways to measure contributions to our shared collective model of our world.

It would be a new way to fund research, and the end result would not be disconnected PDFs, but would be a massive, open, collaborative, structured, simple, computable database. Funders would get thanks embedded in the database and novel methods to measure impact, researchers would get funding, and everyone could benefit from this new kind of open computable encyclopedia.

CancerDB would be a good domain to test this model, as there are already a lot of funders and researchers.

The Copyright Issue

The CancerDB idea also had another advantage. Another contrarian opinion of mine is that copyright law stands in the way of getting the most out of science. The world is flooded with distracting information and misleading advertisements, while some of the most non-toxic information is held back by copyright laws. I thought we could make a point here. We would add all the truest data we could find, regardless of where it came from, and also declare our work entirely public domain. If our work helped accelerate cancer research, we would demonstrate the harm from these laws. I figured it would be hard for copyright advocates to argue for the status quo if by ignoring it we helped save people's lives. As a sidenote, I am still 51% confident I am right on this contrarian bet, which is more confident I ever was in my technology. I have never read a compelling ethical justification for copyright laws, and think they make the world worst for the vast majority of people, though I could be wrong for utilitarian reasons.

The Decision

Once the CancerDB idea got in my head it was hard to shake. I felt in my gut that my approach had merit. How could I keep moving slowly on this idea if it really was a way to advance knowledge and create digital AI experts that could help save people's lives? I started feeling like I had no choice.

The probability of success wasn't guaranteed but the value if it worked was so high that the bet just made too much sense to me. I decided to go for it.

Execution and Failure

A slide from my pitch deck mentioning how these AI experts would be transparent and trustworthy to users and provide researchers with a birds-eye view of all the knowledge in a domain.

Unfortunately, my execution was abysmal. I was operating with little sleep and my brain was firing on all cylinders as I tried to figure this out. People thought I was crazy and tried to stop me. This drove me to push harder. I decided to lean into the "crazy" image. Some said this idea was too naive and simple to work and anyone who thought it would work was not rational. So I was willing to present myself as irrational to pull off something no rational person would attempt.

I could not rationally articulate why it would work. I just felt it in my gut. I was driven more by emotion than reason.

I wanted this attempt to happen but I didn't want to be the one to lead it. I knew my own limitations and was hoping some other group, with more intellectual and leadership capabilities, would see the possibilities I saw and build the thing on their own. I pitched a lot of groups on the idea. No one else ran with it so I pressed on and tried to lead it myself.

I ran into fierce opposition that I never expected. Ultimately, I wouldn't be able to build the organization to build one of these things 100x bigger than PLDB, and prove empirically a novel breakthrough in knowledge bases.

I still had a very fair chance to prove it theoretically. I had the time to discover some algebra that would prove the advantage of this system. Unfortunately, as hard as I pushed myself—and I pushed myself to an insane degree—I would not find that. Like an explorer searching for the mythical fountain of youth, I failed to find my hypothesized algebra that would show how this system could unlock radical new value.

I failed to build a worthwhile second TrueBase. Heck, I even failed to keep the wheels running on PLDB. And because I failed to convince better resourced backers to fund the effort and funded it myself, I lost everything I had, including my house, and worse.

Deep Learning

My confidence in these ideas always varied over the years, but the breakthroughs in deep learning this year drastically lowered my confidence that I was right. I recently read a mantra from Ilya Sutskever "don't ever bet against deep learning". Now you tell me! Maybe if I had read that quote years ago, printed it, and framed it on my wall, I would have bet differently. In many ways I was betting against deep learning. I was betting that curated knowledge bases built by hand would create the best AI experts. The reason why they hadn't yet was that they lacked a few new innovations like the ones I was developing.

Now, seeing the astonishing capabilities of the new blackbox deep learning AIs, I question much of what I once believed.

Arguments Against My Ideas

- There is no reason that knowledge has to be encoded in symbols. Symbols are powerful because they can be shared across time and place, but what ultimately matters is not whether the symbols exist, but whether the skills explained by the symbols are embedded in blackbox neural networks. Symbols can aid learning but the learning is the most important thing. Symbols are just a means to an end. You need to be able to make use of the knowledge. Knowing how to ride a bike is the ends—the knowledge somehow embedded in your neural blackbox—a book on how to ride a bike cannot be more valuable than the blackbox weights themselves.

- There is no reason that symbols have to have an atomic canonical form. If ultimately what matters is that the knowledge is embedded, than how it is stored is not relevant. Concepts don't have to be stored in discrete nodes. They can be stored in superpositions. That could be a more efficient and potentially even truer representation of the concept itself.

- The returns on improving human readable symbolic systems are capped by human biology. Even if you improved human knowledge bases by a large amount, human brains would still be only able to process a minuscule fraction of all knowledge. Blackbox trained neural networks don't have biological caps. The upside to better symbolic networks is capped. The upside to better neural networks is uncapped.

- The opaqueness of blackbox neural networks can be addressed. There could be inspector neural networks that examine other neural networks. These inspector networks will be able to explain the logic behind another networks responses or actions. It might not be a deterministic explanation but it would be arguably better than what we have today. When you ask a question to a human expert today, there is no way to completely audit their answer either. Human brains are also a blackbox. Future neural networks will likely also maintain access to their training data, so could better explain their answers and be less likely to make mistakes.

- If AIs are right often enough it's not so necessary that they be able to show their logic. You might have a whitebox AI that is inspectable but perhaps more difficult to use or give worse answers. If the blackbox one is right 99.99% of the time, then you wouldn't care much about being able to inspect everything under the hood.

- Symbols overvalue two dimensional knowledge. The ability to move your body around is not learned or encoded by symbols, but is essential for keeping you alive. Without symbolic networks, we would be back in the stone age. But without neural networks, we would not be alive. Brains and their learned networks dominate the importance of symbolic networks.

- Static knowledge bases decay. Knowledge is dynamic. The Book would require continual upkeep by human experts and lots of help from tooling. Once learning AIs learn how to learn, they can keep learning on their own and keep their knowledge current. The ideal AI is not the one that starts with the best knowledge, but the one that is the best learner.

The Remaining Case for My Approach

My dumb, universal language, human curated data approach would have merit if we didn't see other ways to unlock more value from all the information that is out there. But clearly deep learning has arrived, and there is clearly so, so much more promise in that approach.

There is always the chance that the thousands of variations of notations and algebras I tried were just wrong in subtle ways and that if I had kept tweaking things I would have found the key that unlocks some natural advantageous system. I can't prove that that's not a possibility. But, given what we've seen with Deep Learning, I now highly discount the expected value of such a thing.

A less crazy way to explore my ideas would be to try and figure out how instead of trying to replace Wikipedia, I could implement these ideas on top of Wikipedia and see if they could make it better. Would adding typing to radically increase the comparability of concepts in Wikipedia unlock more value? That was probably the more sensible thing to do in the beginning.

I could say, a bit tongue in cheek, that the remaining merit in my approach is that a characteristica universalis offers upside without the potential to evolve into a new intelligent species that ends humanity.

Mania Disclaimer

In examining my actions and thinking it is important to disclose that I do have a manic depressive brain.

Last year when I decided to go full throttle on this idea my brain was in a hypomanic, and at points manic, state. That's not the best state to execute in, and my poor execution reflects that.

The downside of hypomania is one can be greatly overconfident in an incorrect contrarian idea. The upside of hypomania is one can have the confidence to ignore the crowd and pursue a contrarian idea that turns out to be correct. It is hard to know the difference.

A related sidenote to the story is that the second "DB" I wanted to build was actually BrainDB. I thought using this system for neuroscience would hopefully help figure out bipolar disorder. An understanding of the mechanisms of bipolar disorder are currently beyond the edge of science. But considering all the factors at the time I judged CancerDB to be the most urgent priority.

Gratefulness

I got my chance. I got to take my shot at the characteristica universalis. I got to try to do things my way. I got to decide on the implementation. Ambitious. Minimalist. Data driven. Open source. Public domain. Local first. Antifragile.

I got to try and build something that would let us map the edge of knowledge. That would power a new breed of trustworthy digital AI experts. That might help us cure problems we haven't solved yet.

I failed, but I'm grateful I got the chance.

It was not worth the cost, but I never imagined it would cost me what it did.

What of the characteristica universalis?

Symbols are good for communication. They are great at compressing our most important knowledge. But they are not sufficient, and are in fact unnecessary for life. There are not symbols in your brain. There are continuously learning wirings.

Symbols have enabled us to bootstrap technology. And they will remain an important part of the world for the next few decades. Perhaps they will continue to play a role, albeit diminished, in enabling communication and cooperation in society forever. But symbols are just one modality. A modality that will be increasingly less important in the future. The characteristica universalis was never going to be a thing. The AIs, artificial continuously learning wirings, are the future. As far as I can tell.

I thought we needed a characteristica universalis. I wasn't sure if it was possible but thought we should try. Now it seems much clearer that what we really need are capable learning neural networks, and those are indeed possible to build.

A characteristica universalis might be possible someday as a novelty. But not something needed for the best AIs. In fact, if we ever do get a characteristica universalis it will probably be built by AIs, as something for us mere humans to play with when we are no longer the species running the zoo.