December 9, 2020 — Note: I wrote this early draft in February 2020, but COVID-19 happened and somehow 11 months went by before I found this draft again. I am publishing it now as it was then, without adding the visuals I had planned but never got to, or making any major edits. This way it will be very easy to have next year's report be the best one yet, which will also include exciting developments in things like non-linear parsing and "forests".

In 2017 I wrote a post about a half-baked idea I named Particles.

Since then, thanks to the help of a lot of people who have provided feedback, criticism and guidance, a lot of progress has been made flushing out the idea. I thought it might be helpful to provide an annual report on the status of the research until, as I stated in my earlier post, I "have data definitively showing that Tree Notation is useful, or alternatively, to explain why it is sub-optimal and why we need more complex syntax."

My template for this (and maybe future) reports will be as follows:

- 1. High level status

- 2. Restate the problem

- 3. 2019 Pros

- 4. 2019 Cons

- 5. Next Steps

- 6. Status of Predictions

- 7. Organization Status

High Level Status

I've followed the "Strong Opinions, Weakly Held" philosophy with this idea. I came out with a very strong claim: there is some natural and universal syntax that we could use for all of our symbolic languages that would be very useful—it would let us remove a lot of unnecessary complexity, allow us to focus more on semantics alone, and reap a lot of benefits by exploiting isomorphisms and network effects across domains. I've then spent a lot of time trying to destroy that claim.

After publishing my work I was expecting one of two outcomes. Most likely was that someone far smarter than I would put the nail in Tree Notation's coffin with a compelling case for why a such a universal notation is impossible or disadvantageous. My more optimistic—but less probable—outcome was that I would accumulate enough evidence through research and building to make a convincing case that a simplest universal notation is possible and highly advantageous (and it would be cool if Tree Notation evolves into that notation, but I'd be happy for any notation that solves the problem).

Unfortunately neither of those has happened yet. No one has convinced me that this is a dead-end idea and I haven't seen enough evidence that this is a good idea[1]. At times it has seemed like a killer application of the notation was just around the corner that would demonstrate the advantages of this pattern, but while the technology has improved a lot, I can't say anything has turned out to be so compelling that I am certain of the idea.

So the high level status remains: strong opinion, weakly held. I am sticking to my big claim and still awaiting/working on proof or refutation.

Restating the Problem

What is the idea?

In these reports I'll try and restate the idea in a fresh way, but you can also find the idea explained in different places via visuals, an FAQ, a spec, demos, etc.

My hypothesis is that there exists a Simplest Universal Notation for Symbolic Abstraction (SUNSA). I propose Tree Notation as a potential candidate for that notation. It is hard to assign probabilities to events that haven't happened before, but I would say I am between 1% and 10% confident that a SUNSA exists and that Tree Notation is somewhat close to it[2]. If Tree Notation is not the SUNSA, it at least gives me an angle of attack on the general problem.

Let's define a notation as a set of physical rules that can be used to represent abstractions. By simplest universal notation I mean the notation that can represent any and every abstraction representable by other notations that also has the smallest set of rules.

You could say there exists many "UNSAs", or Universal Notations for Symbolic Abstractions. For example, thousands of domain specific languages are built on the XML and JSON notations, but my hypothesis is that there is a single SUNSA. XML is not the SUNSA, because an XML document like <a>b</a> can be equivalently represented as a b using a notation with a smaller set of rules.

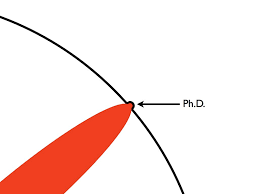

Where would a SUNSA fit?

Inventions aren't always built in a linear fashion. For example, when you add 2+3 on your computer, your machine will break down that statement into a binary form and compute something like 0010 + 0011. The higher level base 10 are converted into the lower level base 2 binary numbers. So, before your computer solves 2+3, it must do the equivalent of import binary. But we had Hindu-Arabic numerals centuries before we had boolean numerals. Dependencies can be built out of order.

Similarly, I think there is another missing dependency that fits somewhere between binary the idea and binary the symbolic word.

Consider Euclid's Elements, maybe the most famous math book of all time written around 2,500 years ago. The book begins with the title "Στοιχεῖα"[3]. Already there is a problem: where is import the letter Σ?. Euclid has imported undefined abstractions: letters and a word. Now, if we were to digitally encode the Elements today from scratch, we would first include the binary dependency and then a character encoding dependency like UTF-8. We abstract first from binary to symbols. Then maybe once we have things in a text stream, we might abstract again to encode the Elements book into something like XML and markdown. I think there is a missing notation in both of these abstractions: the abstraction leap from binary to characters, and abstraction leap from characters to words and beyond.

I think to represent the jumps from binary to symbols to systems, there is a best natural notation. A SUNSA that fits in between languages that let's us build mountains of abstraction without introducing extra syntax.

To get a little more concrete, let me show a rough approximation of how using Tree Notation you could imagine a document that starts with just the concept of a bit (here denoted on line 2 as ".") and work your way up to defining digits and characters and words and entities. There is a lot of hand-waving going on here, which is why Tree Notation is still, at best, a half-baked idea.

.

...

0

1 .

...

Σ 10100011

...

Στοιχεῖα

...

book

title Elements

...

Why would a SUNSA be advantageous?

Given that I still consider this idea half-baked at best; given that I don't have compelling evidence that this notation is worthwhile; given that no one else has built a killer app using the idea (even though I've collaborated publicly and privately with many dozens of people on project ideas at this point); why does this idea still excite me so much?

The reason is because I think IF we had a SUNSA, there would be tremendous benefits and applications. I'll throw out three potential application domains that I personally find very interesting.

Idea #1: Mapping the Frontiers of Symbolic Science

A SUNSA would greatly reduce the cost of a common knowledge base of science. While it may be possible to do it today without a SUNSA, having one would be at least a one order of magnitude cost reduction. Additionally, if there is not a SUNSA, than it may take just as long to come to agreement on what UNSA to use for a common knowledge base of science as it would to actual build the base!

By encoding all of science into a universal syntax, in addition to tremendous pedagogical benefits, we could take analogies like this:

And make them actual concrete visualizations.

Idea #2: Law (and Taxes)

This one always gets me excited. I believe there is a deep connection between simplicity, justice, and fairness. I believe legal systems with unnecessary complexity are unfair, prima facie. While legal systems will always be human-made, rich in depth, nuanced, and evolving, we could shed the noise. I dream of a world where paychecks, receipts, and taxes are all written in the same language; where medical records can be cut and pasted; and where when I want to start a business I don't have to fill out forms in Delaware (the codesmell in that last one is so obvious!).

I believe a SUNSA would give us a way to measure complexity as neatly as we measure distance, and allow us to simplify laws to their signal, so that they serve all people, and we don't suffer from all that noise and inefficiency.

Idea #3: Showcasing the Common Patterns in Computing From Low Level to High Level

I love projects like godbolt.org, that let you jump up and down all the levels of abstraction in computing. I think there's an opportunity to do some incredible things if there is a SUNSA and the patterns in languages at different layers of computing all looked roughly the same (since they are roughly the same!).

What would the properties of a SUNSA be?

Tree Notation might not be the SUNSA, but it has a few properties that I think a SUNSA would have.

- 2 or more physical dimensions: Every symbolic abstraction would have to be contained in the SUNSA, so to include an abstraction like the letter "a" would require a medium have at least more than one physical dimension.

- Directional: A SUNSA would not just define how symbols are laid out, but it would also contain concepts of directionality.

- Scopes: Essential for growth and collaboration.

- Brevity: I think a SUNSA will have fewer components, not more. I often see new replacements for S-Expressions or JSON come out with more concepts, not less. I don't think this is the way to go—I think a SUNSA will be like a NAND gate and not a suite of gates, although the latter are handy and pragmatic.

I also will list one thing I don't think a SUNSA will have:

- A single entry point. Currently most documents and programs are parsed start to finish in a linear order. With Tree Notation you can parse things in any order you want—start from anywhere, move in any direction, or even start in multiple places at the same time. I think this will be a property of a SUNSA. Maybe SUNSA programs will look more like this than that.

So those are a few things that I think we'll find in a SUNSA. Will we ever find a SUNSA?

Why might there not be a SUNSA?

I think a really good piece of evidence that we don't need a SUNSA is that we've seen STUPENDOUS SUCCESS WITH THOUSANDS OF SYNTAXES. The pace of progress in computing in the 1900's and 2000's has been tremendous, perhaps because of the Smörgåsbord of notations.

Who's to say that a SUNSA is needed? I guess my retort to that, is that although we do indeed have thousands of digital notations and languages, all of them, without exception, compile down to binary, so clearly having some low level universal notation has proved incredibly advantageous so far.

2019 Pros

So that concludes my restatement of the Tree Notation idea in terms of a more generic SUNSA concept. Now let me continue on and mention briefly some developments in 2019.

Here I'll just write some bullet points of work done this past ~ year advancing the idea.

- Types and Cells

- Tree Notation as a Subset of Grid Notation

- New homepage

- TreeBase

- CopyPaster

- Dozens of new Tree Languages

- More feedback than ever. Tens of thousands of visitors. Hundreds of conversations.

2019 Cons

Here I just list some marks against this idea.

- It still sucks.

- No killer app yet.

- No good General Purpose Tree Language.

- No good Assembly Tree Language.

- No good LISP Tree Language.

- No good LLVM IR tie in yet.

- One argument put to me: "there's no need for a universal syntax with deep learning—complexity IS the universal syntax."

- Another argument put to me: "sure it is still simple BUT there are 2 types of inventions: ones that get more complex over time and ones that no one uses"

Next Steps

Next steps is more of the same. Keep attempting to solve problems by simplifying the encoding of them to their essence (which happens to be Tree Notation, according to the theory). Build tools to make that easier and leverage those encodings. This year LSP will likely be a focus, Grid Notation, and the PLDB.

Tree Notation has a secret weapon: Simplicity does not go out of style. Slippers today look just like slippers in Egypt 3,000 years ago

Status of Predictions in Paper

My Tree Notation paper was my first ever attempt at writing a scientific paper and my understanding was that a good theory would make some refutable predictions. Here are the predictions I made in that paper and where they stand today.

Prediction 1: no structure will be found that cannot serialize to TN.

While this prediction has held, a number of people have commented that it doesn't predict much, as the same could really be said about most languages. Anything you can represent in Tree Notation you can represent in many encodings like XML.

What I should have predicted is something along the lines of this: Tree Notation is the smallest set of syntax rules that can represent all abstractions. I think trying to formalize a prediction along those lines would be a worthwhile endeavor (possibly for the reason that in trying to do what I just said, I may learn that what I just said doesn't make sense).

Prediction 2: TLs will be found for every popular 1DL.

This one has not come true yet. While I have made many public Tree Languages myself and many more private ones, and I have prototyped many with other people, the net utility of Tree Languages is not high enough that people are rushing to design these things. Many people have kicked the tires, but things are not good enough and there is a lack of demand.

On the supply side, it has turned out to be a bit harder to design useful Tree Languages than I expected. Not by 100x, but maybe by as much as 10x. I learned a lot of bad design patterns not to put in Tree Languages. I learned that bad tooling will force compromises in language design. For example, before I had syntax highlighting I relied on weird punctuation like "@" vs "#" prefixes for distinguishing types. I also learned a lot of patterns that seem to be useful in Tree Languages (like word suffixes for types). I learned good tooling leads to simpler and better languages.

Prediction 3: Tree Oriented Programming (TOP) will supersede Object Oriented Programming.

This one has not come true yet. While there is a tremendous amount of what I would call "Tree Oriented Programming" going on, programmers are still talking about objects and message passing and are not viewing the world as trees.

Prediction 4: The simplest 2D text encodings for neural networks will be TLs.

This one is a fun one. Definitely has not come true yet. But I've got a new attack vector to try and potentially crack it.

Status of Long Bet

After someone suggested it, I made a Long Bet predicting the rise of Tree Notation or a SUNSA within ten years of my initial Tree Notation post. Clearly I am far off from winning this bet at this point, as there are not any candidate languages even noted in TIOBE, never mind in the Top 10. However, IF I were to win the bet, I'd expect it wouldn't be until around 2025 that we'd see any candidate languages even appear on TIOBE's radar. In other words, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

As an aside, I really like the idea of Long Bet, and I'm hoping it may prompt someone to come up with a theoretical argument against a SUNSA that buries my ideas for good. Now, it would be very easy to take the opposing side of my bet with the simple argument that the idea of 7/10 TIOBE languages dropping by 2027 won't happen because such a shift has never happened so quickly. However, I'd probably reject that kind of challenge as non-constructive, unless it was accompanied by something like a detailed data-backed case with models showing potential speed limits on the adoption of any language (which would be a constructive contribution).

Organization Status

In 2019 I explored the idea of putting together a proper research group and a more formal organization around the idea.

I put the breaks on that for three reasons. The first is I just don't have a particularly keen interest in building an organization. I love to be part of a team, but I like to be more hands on with the ideas and the work of the team rather than the meta aspect. I've gotten great help for this project at an informal level, so there's no rush to formalize it. The second reason is I don't have a great aptitude for team building, and I'm not ready yet to dedicate the time to that. I get excited by ideas and am good at quickly explore new idea spaces, but being the captain who calmly guides the ship toward a known destination just isn't me right now. The third reason is just the idea remains too risky and ill-defined. If it's a good idea, growth will happen eventually, and there's no need to force it.

There is a loose confederation of folks I work on this idea with, but no formal organization with an office so far.

Conclusion

That's it for the recap of 2019! Tune in next year for a recap of 2020.

Related Posts

- Why Scroll? (2024)

- Microprogramming: A New Way to Program (2024)

- Particle Chain: A New Kind of Blockchain (2024)

- ETA!: A Measure of Evolution (2024)

- CheckBox: An Online + Offline Voting System (2024)

- The World Wide Scroll (2024)

- Download this Blog (2024)

- ICS: A Measure of Intelligence (2024)

- PTCRI: An Equation about Syntax Potential (2024)

- Patch: a micro language to make pretty deep links easy (2024)

- What can we learn from programming language version numbers? (2024)

- ScrollSets: A New Way to Store Knowledge (2024)

- Hot Coffee (2024)

- Final Tree Notation Report (2024)

- Words are Worse than Weights (2024)

- I thought we could build AI experts by hand (2023)

- A Proposal to Solve Government Forms Worldwide, Forever (2023)

- Use the Spine (2023)

- One Textarea (2022)

- Root Thinking (2022)

- Aftertext (2021)

- Scrolldown now has Dialogues (2021)

- The Public Domain Publishing Company (2021)

- Scroll Beta (2021)

- Building a TreeBase with 6.5 million files (2020)

- Dataset Needed (2020)

- Type the World (2020)

- Dreaming of a Data Checked Language (2020)

- Removing the 2’s from Trinary Notation is a Terrible Idea. (2019)

- PAC: Particle Atom Complexity (2017)

- Parsers: a language for making languages (2017)

- Ohayo (2017)

- A New Discovery in Computer Science: 2-Dimensional Programming Languages (2017)

- Tree Notation: an antifragile program notation (2017)

- NudgePad: An IDE in Your Browser (2013)

- ScrollNet: A successor to the Internet (2013)

- Introducing Note (2012)

Notes

[1] Regardless of whether or not Tree Notation turns out to be a good idea, as one part of the effort to prove/disprove it I've built a lot of big datasets on languages and notations, which seem to be useful for other people. Credit for that is due to a number of people who advised me back in 2017 to "learn to research properly".

[2] Note that this means I am between 90-99% confident that Tree Notation is not a good idea. However, if it's a bad idea I am 40% confident the attempt to prove it a bad idea will have positive second-order effects. I am 50% confident that it will turn out I should have dropped this idea years ago, and it's a crackpot or Dunning–Kruger theory, and I'd be lying if I said I didn't recognize that as a highly probably scenario that has kept me up some nights.

[3] When it was first coming together, it wasn't a "book" as we think of books today and authorship is very fuzzy, but that doesn't affect things for my purposes here.